Pat Stuart

Books and Columns

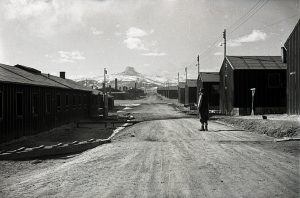

The camp when still an internment center.

Heart Mountain Camp – Winter Comes

by Pat Stuart

Powell Tribune, 30 April 2019

The story of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center’s second and largely unknown life, as seen through my now nine-year-old eyes, continues.

“Powell has more buses than any other school district in America,” my father said at some point after I started in my new school, Powell Elementary. Seeing them waiting for us every morning and afternoon made a believer out of me. There couldn’t be more busses than that in the whole world.

Not as many as we’d seen in early September, though, for a steady flow of sections of black-coated barracks’ sections had been wheeling down the hill toward the highway at the rate of several a day. The homesteader families who owned them went, too, while the school district kept adjusting its bus routes. Still, there were a lot of us Bureau kids and not a few homesteader ones huddled against the wind and the sharp cold every morning, waiting, with Heart Mountain’s sole visible peak seeming to brood above the long rows of black-coated barracks.

Come rain or shine, snow or melt, the busses arrived. Until they didn’t.

Christmas at the camp saw an avalanche of festivities. Most of the families were young, everyone from somewhere not Wyoming, while the husbands were veterans of WWII and accustomed to base living with its organized activities. Arriving at Heart Mountain must have seemed like a second verse to a military song for them. Later, after being part of an overseas’ embassy community, I saw another similarity. The local Bureau chief was the equivalent of our ambassador, and his wife led the other wives. Natural leaders sprang up to take on self-appointed functions, and everyone pitched in to help.

So, we had clubs—everything from chess to pinochle, from knitting to books. We had a pre-school and Sunday school, and the pre-school program had a rhythm band; the kids in uniforms made by moms. We had Bible studies, a dance band and, probably, a choir, too. We had Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops not to mention Cub Scouts and Brownies. A lending library (honor system) appeared in the Rec Hall. Lectures were popular in this pre-Google period. My father was particularly enthusiastic about one on Wyoming hunting laws and the best hunting areas, but there were what seemed like lots of other kinds of ‘how to’ talks that winter.

Activities

The men organized car pools to go to work; the women organized car pools for every other kind of trip to either Cody or Powell. If you wanted to go to town to shop or attend a movie or whatever, you’d check a board in the Rec Center first. Saving on gas was important, even at twenty-seven cents a gallon. Grocery shopping seemed an exception since we bought in Ralston where a Quonset hut had been turned into a supermarket.

No one had money to spare and, if they did, it went into savings accounts. The adults were depression babies who knew the “value of money.” In fact, those three words figured into almost every conversation even though it was socially incorrect to talk about money or muse aloud about how much of it any particular person might have. In short, by today’s standards, we were all poor.

Yet, we considered ourselves to be solidly middle class, and I believe we were seen that way by others. All of which I mention because it strongly influenced our Christmas—one very short on presents and very long on visiting and hospitality and community activities.

Like my father and his instrument-playing buddies with their weekly jamming sessions; crammed into our tiny living room (standing room only), jostling against the scrawny Christmas tree but happy with their swigs of whiskey, bowls of popcorn, and music.

We walked across the parade ground at least once during that Christmas season to a country dance in the Rec Hall. The babies and toddlers went into the cloak room under the eye of kids my age. As for us, we rotated. Dancing with Dad was big for us. We would dosey-doe and allemande-left with enthusiasm.

Weather

The real disappointment that Christmas was a paucity of snow. My father had brought his sled from Oregon where, in past years, we’d gone up Mount Hood to enjoy sledding with as many as four of us crammed on a sled meant for one. Surely, Wyoming with its mountains, would have sledding. Not.

We drove up the North Fork one day looking for some place … any place and, while I remember seeing snow, none of it offered a proper downhill run or had the quality to sled on. An incipient snowball fight ended as snow scooping. You couldn’t even make a snowman out of the stuff.

What kind of place was this?

As for sledding at the camp? Forget it. The wind had scoured the ground of what little snow we’d seen so far that winter, leaving snow tails on sagebrush clumps to make our “white Christmas.”

Even the kids, who were as a rule quite happy living at the camp, could complain about the lack of snow. And, did.

Until January 2, 1949.

“No school tomorrow,” Daddy probably said as we went to bed that Sunday night with a storm raging outside, the wind turning our windows into flutes that played in a keening, high register. The walls threatened to buckle under the onslaught, every gust a bit more ferocious than the last; the coal stove in the living room (our one source of warmth) burned red but failed to heat much of anything. Mom rolled up towels to jam against the doorsills to keep the snow out. We wrapped ourselves in blankets, I read, and Mom and Dad fiddled with the radio that had stopped broadcasting much of anything except static. https://patstuart.com/heart-mountain-a-kid-paradise

Ideas and words to provoke thought…