Pat Stuart

Books and Columns

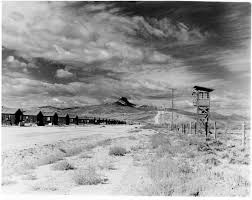

Heart Mountain Camp – A Kid Paradise

by Pat Stuart

Powell Tribune, 16 April 2019

Little has been written about the WWII Japanese internment camp, the Heart Mountain Relocation Center’s second life. Located between the NW Wyoming towns of Powell and Cody and turned back to the Bureau of Reclamation by Congress, it continued to be occupied by homesteaders and Bureau employees until 1951. What had been home to some 11.000 Japanese, became headquarters for a final push to fulfill Buffalo Bill Cody and Theodore Roosevelt’s vision of bringing water to 120,000 acres in the Big Horn Basin. To that end, once the Japanese had been moved out, the Bureau began hiring staff and advertising for homesteaders, attracting recently demobilized veterans to work on and homestead the Heart Mountain Division of the Shoshone Project.

Both staff and homesteaders came as families, moving into the recently abandoned housing. And, thus, the Relocation Center gained a new, if temporary, life. This and the next several columns describe a pre-teen’s experiences during three years in what sometimes seemed heaven; sometimes hell.

This Was the West?

We were moving to Wyoming, the real west, the land of cowboys and Indians, of bears and antelopes. Dad was waiting when Mom, having driven us from Oregon, pulled our 1939 Plymouth coupe to a stop in front of our new home—Unit 1, Goat Hill, Heart Mountain Relocation Center.

Mom’s expression turned bleak as she looked around at rows of black barracks stretching toward a stub of a mountain, at fencing around a power sub-station embedded with tumbleweeds, at the treeless and barren ground. She would come to love Heart Mountain and the land, but that day in the spring of 1948 she only said, “Oh, Al,” to my father, Alvin Reher.

At eight, I knew enough to understand her reaction to the grim and dismal surroundings and to our apartment’s interior with its water-stained walls, windowsills sporting dusty hills, the heavy smell of coal fires, and the mineral-encrusted sinks, tub, and toilet bowl.

“Oh, Al,” Mom was to say often in coming days.

Our Home

But, her problem was not ours. The Relocation Center might be grim … all browns and greys under a blue dome … all keening wind blowing dirt about … but it came clear straight away that we had moved to a kid paradise.

Unit 1, Goat Hill was a miniscule three-bedroom apartment, one of three units in our barracks and the same in some particulars as the barracks occupied by the Japanese. That said, the differences were striking. We had a kitchen and bathroom, both just large enough to flap your elbows but there. We had asbestos-based Celotex wallboard, shingles on the outer walls, linoleum laid over the floorboards, and running water.

Compared to what the Japanese had called home, it was pure luxury.

A Massive Playground

The Jap Camp, as everyone called it (not understanding how politically incorrect they were), also had a kid around every corner. Not just those belonging to the dozens of newly arrived Bureau of Reclamation families but homesteader kids whose parents had drawn allotments and who were living at the camp until they could move the two barracks that went with their new land.

Our playground spread for acres, farther than we cared to run in every direction, with something exciting and interesting just around the next corner, for the Camp was still mostly intact. Its public buildings remained: empty and loosely secured with some of their former fixtures left behind. We could play hospital in the hospital, school in the school, and office in the office building, and so much more.

We ran barefoot and wild, the soles of our feet toughening up on ground that was essentially a gravel pit held together by blow dirt.

“Come on, they’re taking down the jail.” That call took everyone who heard it on the run to a building that we called the jail, probably because they kept it locked up tight. We were avid to see inside. I got there too late. All that was left was the basement which was divided into sections by doorless concrete walls.

Wait a minute. A basement? No building in this place had a basement.

“They lowered the prisoners down there through holes in the floor,” one of the bigger kids said. “Those are the cells.”

I believed it but, then, I believed another building had been a crematorium.

“That’s where they burned the bodies,” older kids said of a brick something-or-other in the middle of a warehouse-like structure. A dummy hanging from the rafters underscored the point. It was totally and satisfyingly scary. And why should I doubt? I’d heard about the concentration camps in Germany, and we all knew this place had been a concentration camp for “the Japs,” as the adults called the former inmates. If the Nazis had ovens in their camps, then it seemed reasonable to think that we would have them, too. No moral quibbling for us.

Danger

More fun than anything were the guard towers. The ladders had been removed by someone who knew nothing about kids. No ladders? Well, clearly, we were meant to climb the crossbeams. Who needed a jungle gym; we had the towers until Andrea Hull fell and shattered a bone in one arm.

A few days later only bare ground remained where the towers had been. No more could we brave splinters in our hands and legs to reach the top with our sandwiches where we played at being guards. “Kapow! Got him trying to escape!” We also lost the visual reminder that this had been a prison, and we missed that. Gone was that special frisson of reality when making up stories of prisoner and guards in the shadow of what we thought had been the real thing.

The “H” shaped camp administrative headquarters stood just behind a monument (built to honor the Japanese soldiers who volunteered and fought in WWII) and only a minute away from our front door. The War Authority and Bureau had cleared out without clearing up. Its offices had desks and cabinets and reams of paper forms. While pretending to be office workers had a short lifespan among me and my friends, the linoleum flooring and long halls made for great skating and perfect hopscotch layouts.

Playing school was about as unpopular as the rattlesnakes that we were convinced lived under every barracks. What the school offered instead was totally spectacular; was a basketball court with a highly polished oak floor and baskets mounted at either end. None of my friends owned a basketball, but where there’s a will, there’s a way. We used any and every kind of ball we could find to “shoot hoops.”

Sports

There was a swimming “hole” about a five-minute walk away at the other end of Goat Hill, one the adults claimed to be full of leaches. “You get in that water, Patty,” Daddy said, “and the bloodsuckers will be all over you.”

I didn’t get in the water, which looked like nothing but mud, anyway.

Other Kinds of Play

Some kids played tennis after a fashion on a concrete court behind our unit–between it and the main road. I say “after a fashion” since the concrete had developed cracks of various widths that invited twisted ankles and that sent balls spinning in unintended directions. Still, as an eight-year-old just off an Oregon farm, that court was heaven.

Not for tennis. We couldn’t afford either rackets or balls, but for skating. Santa had given me a pair of skates of the kind you can only read about now. They were wheels on a frame, the frame fitting to the shoe, then clamped into place with a skate key. (There’s a bit of historic trivia for you.) Before we figured out how to jimmy a door and get into the Admin Building to skate those halls, that tennis court was just the thing.

Our first summer ended the day a long convoy of buses down-shifted, engines roaring, to climb the hill and pull onto what, I’m guessing, had been the War Authority’s parade ground. One by one the growling, belching transports left the road to circle the field. They came to a stop—a great, long yellow snake come to carry us out of kid paradise.

Ideas and words to provoke thought…