Pat Stuart

Books and Columns

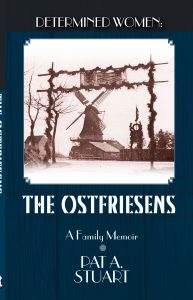

DETERMINED WOMEN – THE OSTFRIESENS

Iccka Eilerts Buss, a young mother with four children under the age of six, one still in arms, emigrated to the sodden still-virgin prairies of southern Illinois in the mid-nineteenth century. From the cold, wet verges of the North Sea through the terrors of a tiny, death-ridden immigrant ship, its hold stacked with human cargo, she kept her family together. But within a month of their arrival, her youngest daughter and a nephew were dead, another nephew was permanently crippled, her husband suffered a serious accident, and she had the responsibility of providing shelter and caring for him and her remaining children to ensure they neither starved nor froze. She accomplished this and much more. Twenty years later, ten years after her husband’s death, she was one of the most successful farmers in Adams County, Illinois.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Like thousands of other immigrants seeking opportunity in the United States, Ickka Eilerts Buss endured incredible hardship with courage, perseverance, ingenuity, and a list of lesser qualities–lesser only when survival for themselves and their children is the core goal. Above all, they were determined.

No other photo than this one of Iccka Buss survives. We can see only the bones of what was once a lovely young woman. Perhaps that is just as well since in the set of the mouth, the piercing quality of the eyes, we can read what she endured as well as the compassion and love that earned her the nickname “Moder” or mother in her community.

Today, her 3rd, 4th, and 5th great grandchildren are spread across the United States, but the core still found in the town she helped to found– Golden, IL. The Elizabeth, its hold packed with human cargo.

The Elizabeth, its hold packed with human cargo.

CHAPTER ONE

1838, Westerende, Ostfriesland

“Go to Ostfriesland and you will understand. It is the land and the sea that shape us.”

–Ickka Eilerts Buss

She was like one of the sparks flying upwards from the bonfire, weightless, and capable of climbing with them into the night sky, mesmerized by the sound of strings and drums, by the beating of clogs on bare earth. Strands of hair had escaped from under her mop cap, competing with the flaring brilliance of the firelight. Around her other girls danced with their young men. Older men lounged outside the pub, mugs in hand. Older women tapped their toes and waited for the music and drink to catch their men, to erase a year of worry and work.

So we can imagine that May Day of 1838. The beer flowed, the music worked its magic. Serious talk among the men slowed and trailed away. One by one they grabbed a woman of choice with their rough, gnarled hands and leaped into the circle around the village May Pole—a tall Birch profusely and profanely decorated with green branches and paper flowers. On Sunday they would trail soberly into church. But on this one night of the year the people whirled and stomped and celebrated the coming of spring and the renewed fertility of earth and its creatures in the old way. Urges suppressed for 364 days surfaced. There was a reason that the mid-wife had to rush from house to house in February.

This May Day thing. The Lutheran churches of Ostfriesland deplored its excesses, condemning the wild immorality of the event. But, wisely, the church authorities did nothing to stifle the custom, for while Ostfriesians might have centuries since converted to Christianity and rigidly adhered to its forms, they had singularly failed to accept the church’s views on two subjects—sex and alcohol. So on feast days the people drank and enjoyed sex outside the marriage bed and, quite often, went to the altar gloriously pregnant. The dancing girl’s mother was a case in point, having delivered her just six days after saying her vows.

The girl, Ickka Eilerts was eighteen, and it’s likely she could cavort with the best of them. Her nubile if overly thin and muscular flesh sat comfortably on a straight back and long, strong legs capable of carrying her through the entire night of festivities. Hair with red highlights, parchment white skin, and blue eyes contrasted with the deep blues and dark browns of the surrounding night, creating a scene worth of a Flemish painter—a van Dyck or Rubens.

It’s entirely possible that Jann Gerdes Buss, a tall but stocky single man from a village less than two miles distance, met Ickka Eilerts for the first time on this one day of unfettered celebration in Westerende. But probably not. More likely, he’d often seen her when he moored his boat in the village’s small marina—a widened place on the big canal connecting one of Ostfriesland’s larger towns with the North Sea port of Emden.

Presuming he was there that May Day night, Jann would have mingled with the older men for the first hours as was proper given his economic status as landowner and boat captain. He would have shared their talk about the affairs of the day, letting the anticipation for the dance, for the sexuality of touch and movement build, all the while watching Ickka and the other girls dancing in the firelight as their hair came loose from their caps and flashed about their faces. Then when the tension was irresistible, he would have jumped into the circle, grabbing one of them by the waist, twirling his choice around and feeling her hair whip his against his face, inflamed by the night and his needs.

Jann’s ultimate attention to Ickka, no matter what the circumstances of their first encounter, was welcome for he was a most eligible bachelor. Among the poverty-stricken homes belonging to the Eilerts and their friends this meant a great deal. Jann, while still relatively young, earned a good living sailing the local canals, picking up produce to deliver to the larger towns and returning with domestic necessities, including that marvelous beverage, tea. He also owned and worked several small parcels of land alongside hired day laborers.

As for Ickka’s father, he was firmly settled on the bottom rung of the Friesian social structure, a place of no real hope but at the same time of no shame. It was a status he shared with the majority of Friesians. “That which doesn’t kill you, strengthens you,” might have been his slogan. Gert Eilerts was a survivor from a long line of survivors.

He’s referred to as a “warfman” and a “colonist,” meaning he cut peat and did a bit of farming. In point of fact, he supported himself and his family any way he could. He probably dug ditches and dredged small canals to drain bog and swampland for others, then cut and harvested the thick vegetative matter left behind. He would have loaded peat into canal boats, putting the “white peat,” the fertile top soil back in place so he could plow it, plant it, and harvest crops of buckwheat, earning in a good year just enough to feed his family. Gert Eilerts understood work.

No matter the economic status, an Ostfriesan working man was proud and independent, thought of himself as neither serf nor peasant. In principle, he lived where he wanted; moved where he would. In principle, he met with his peers to decide local matters. The hard reality, though, was that a man’s economic situation governed what he could and could not do. While the feudal system never long imposed its heavy hand on Ostfriesians, overpopulation, land scarcity and a subsistence economy did what force failed to accomplish—it divided the people into classes which kept those at the bottom forever locked into a cycle of poverty. Their reality was stark and unforgiving. While they could move about physically and did, seeking work wherever they could find it, there was barely more hope for them of social mobility than there was for a serf in the Rhineland.

Thus, Gert and Janna Eilerts and their brood were lodged at the bottom of the bottom, forever struggling for the daily essentials. Jann Buss, on the other hand, was somewhere in the middle class and had prospects. As a trader, freight hauler, and boat and land owner he already sat with others of his economic status to advise and vote on matters actually decided by the topmost of Ostfriesian classes. These latter were the clergy, judges, and teachers, the wealthier landowners, rich merchants, and—most particularly—the nobility.

New Year’s Eve 1838

If Jann was as close to Prince Charming as Ickka could hope to find, he left no evidence of needing a princess over the next months. He may, though, have used the Westerende moorings to overnight his boat, seeing Ickka before walking the short distance to his own village of Ludwigsdorf, although it seems likely he preferred the slightly closer mooring just to the west of his home outside the village of Ihlowerfehn.

At the moment, though, he had no particular need for a wife and no lack of female companionship when he wanted it. And why would he care to marry a girl who’d bring nothing of any value to the marriage, anyway? He’d gain absolutely nothing from such a liaison but a wife.

Still, even if Jann kept his Ilhowerfehn base, he would have been reminded of the tall, strong young woman every time he sailed the canal between Aurich and Emden, passing Westerende, perhaps inventing reasons to pause and enjoy a glass of beer at the tavern where he might spot Ickka passing.

The Buss family home in Westerende, Ostfriesia, Germany

Then, Jann’s circumstances changed. He was the youngest of five children born to Gerd Berens Hinrichs Buss and his wife Elsche Catharina Janssen Flesner Buss. They’d had five children—three boys and two girls—of whom Jann was the youngest. Hinrichs, the oldest boy, had long since married and set up his own household. Next Weert had wed and moved with his new wife, Ahrendji, to a small farm the young couple had been given. Likewise, both girls had married and left home. By 1838 all of the siblings lived within an hour’s walk of Ludwigsdorf, but only Jann was still at home when his parents began failing.

By that time the old folks had already retired and turned over the bulk of their businesses to their boys. Now, perhaps to secure their own care, Gerd and Elsche gave Weert and Jann their last piece of farmland—the equivalent of about three acres.

Whatever the arrangement between parents and sons, Weert and his wife Ahrendji moved back into the family home. During the next year, Weert and Jann continued their usual work routines while Ahrendji took care of the old folks, the house, animals, and an acre of garden around the house. Then, two things happened. Mother Elsche died and Ahrendji became pregnant with her first son.

Did Jann’s aged father need more care than Ahrendji felt she wanted to provide? While it was customary for the wives of the sons to fit into the household and take on whatever burdens went with it, something was different this time. Was Ahrendji’s health bad? Perhaps Jann and Weert quarreled?

In any event, Weert and Ahrendji moved out after reaching an agreement with Jann over the division of the three-acre parcel and a share-out of the old man’s remaining property. Jann was certainly not unhappy with this outcome which made him sole owner of a large house and its acreage in addition to his other holdings. Yet, he now also had sole responsibility for his father as well.

How to manage when his source of income kept him moving around the country, often away from home for days at a time? In all likelihood he expected his sister, Gesche, who lived with her children and husband in the same village, to step in and care for Father Gerd. He may also have paid her husband—who was a laborer on a par with Ickka’s father—to farm his land and mind his animals. This seems, in fact, to have happened. But, again, the arrangement must have been unsatisfactory because Jann finally went looking for a wife.

What were his criteria? Sex didn’t figure into the equation. Sex was easily available. Love or passion? Unlikely, as he’d passed that first period of strong youthful emotions. No. He needed a hard, biddable worker who had proven herself capable of all the housewife’s skills plus had experience caring for animals and gardens. And the sooner he found such a one the better.

He was not looking for beauty and wouldn’t get it with Ickka Eilerts. She was on the tall side, even for Ostfriesians, with large hands that had roughened in the early winter but had yet to redden and ulcerate. Her face was a long, pleasing oval. Her milky complexion had been rouged by cold. As for her features, her nose was a bit thick but well-proportioned for her visage. Her lips were generous and full. With a different upbringing, her eyes might have made her beautiful, but even at eighteen they had lost any hint of softness and taken on a hard, determined look, were almost fierce, were definitely riveting. Her shoulders weren’t particularly broad, were almost narrow.

None of this mattered. Jann wasn’t looking to find the sort of women he saw in Aurich who curled their hair, powdered their faces, played musical instruments, and sat at home embroidering or making lace.

It seems likely, therefore, that Jann took himself to Westerende on New Year’s Eve of 1838 for Spec und Dikken or “bacon and pancakes.” But this occasion was about a great deal more than food. Here was an opportunity to see if the girl had an interest in him and to head off any other possible suitors, for at eighteen Ickka was as good-looking as she’d ever be while Jann’s shopping list of desirable marital traits was no different from that of many other men. And who could tell where her fancy might have fallen? There might even be other boat captains who’d seen her or danced with her or even had sex with her. On the other hand, she would bring nothing to the marriage except herself, which ruled her out as marriage material for most men of property … well, to be blunt about it … men without the need to combine nurse, servant, farm hand, and wife in one package.

Yet, Jann couldn’t be sure he had no rivals. So he probably went to Westerende on New Year’s Eve as a suitor.

One can only imagine how Frau Eilerts’ heart must have fluttered when Jann’s tall figure loomed in her doorway on that or some other day. The fact that he was there spoke volumes.

“Moins,” Janna Eilerts would probably have stammered the usual Plattdeutsch greeting, standing aside but no doubt wishing she could mask the bare interior of her home. Still, she and her daughter were waiting for possible visitors. It was, after all, New Year’s Day. Both would have put on clean aprons after baking the best Spec und Dikken (bacon pancakes) in all of Ostfriesland … or so Janna probably told herself while settling her breathing after seeing just who had come to her door.

Why do we think Jann visited the Eilerts on this particular day?

Because it was a day for lovers, a day that often ended with a marriage proposal and a wedding. The timing is right for that to have been the sequence for Jann and Ickka.

New Year’s Eve had evolved into a sort of Sadie Hawkins Day among the Ostfriesians. Men could take the initiative or a young woman could invite the man or men of her choice into her home to drink beer and share her bacon pancakes. If she chose, she could even propose to him. More subtly she could arrange for him to receive a pancake with seven spec’s (pieces of bacon), which meant he had found his true love and ought to propose to her.

Janna Eilerts, if not Ickka herself, certainly made sure that Jann received the pancake with seven specs. Did Ickka also propose? In this instance, it wasn’t necessary nor is it certain that she might not have preferred to marry someone else.

What is certain is that the formalities soon followed. If they held to tradition, Jann would have made a series of visits to the house and been left alone with Ickka and a candle, one placed in a special holder with five or six adjustable rings kept or borrowed for the occasion. The rings were like an egg timer, set to a predetermined time. When the candle burned down to the designated ring, the visit was over. In this way, the father could tell a suitor just how welcome his visit was. Without doubt, Gert Eilert would have tapped the bottom ring on this occasion. “Here is the time,” he would have said with a wide grin and, possibly even, a wink.

The affair might have been settled on New Year’s Eve, but given the timing of the wedding the process seems to have been a bit slower. It’s more likely that Jann proposed in another traditional way, during a separate formal visit and accompanied by one or more friends.

If so, on that seminal day Jann and a friend would have scraped the mud from their boots, then entered the Eilerts’ home which probably consisted only of one room in which the family slept, ate, occasionally bathed and worked. Bending their heads to pass under the low lintel, they would’ve had to squint to see in the hut’s smoky dim interior, sniffing appreciably at the smell of porridge seasoned with leaks or something similar simmering over a peat fire. They would not have noticed how steam from the cooking pot mingled with the reek of unwashed human bodies, moldy reed roofing, and damp ground, for the Eilert home was probably nothing more than a mud and wattle hut built on an ancient model, sufficient to keep the elements somewhat at bay but offering little comfort.

No one ever noticed the rancid air. That’s the way it always was in such houses, a mix that also included the fragrance of the burning peat, the ammoniac stench of manure moldering in the attached byre, and the rich odor of wet peat and clay earth in the fields.

Background sounds, too, were unnoticeable in their normality. The big canal that passed the village washed its banks as it always did. Rain often pattered on puddles, plopped off the bundled roof reeds and, as an occasional gust of wind caught a shower, it splattered drops against the cottage’s north side. The poultry and whatever animals the Eilerts might’ve been fortunate enough to own that year would’ve stirred in their rude lean-to under the Eilerts’ roof. Certainly, the fire munched in a contented way at the peat.

The men, their stools drawn close to the hearth, would have held mugs in big, callused hands, while they drank and talked of larger affairs, of the new railroad that connected Amsterdam to Haarlem and how extending the rail lines would affect the canal boat business. As the day faded outside, the room darkened, and the fire reflected on their faces. Their florid complexions seemed yellow. Their hair grew gold highlights, and they probably spoke of Victoria, who had inherited Hannover and, thus, Ostfriesland. Salic law, everyone was saying, made her rule illegal. A woman emperor? Impossible. “It can’t last,” they agreed. “The Hannoverians will choose a new king.”

Finally, having covered all of the important matters of the day, with fresh mugs of beer in their hands, they would have considered the marriage offer, ticking off the essential points. Like:

“Jann has checked with the church,” the friend might have said, taking another deep drink of the Eilerts’ beer, a brew Ickka and her mother would’ve made from the buckwheat that everyone grew.

“I can think of no family connection in my lifetime,” Gert might have replied. A check of church records was a required step in the run-up to a wedding because Ostfriesians generally only married other Ostfriesians and bloodlines had become confused over the past several thousand years. No consanguinity within three generations was the rule.

Next, there was the question of pregnancy.

The friend might have glanced at Ickka, who was most likely still about her evening chores, her workday running from before dawn to after dark. Was she pregnant? Hard to tell in the clothing of the day, nor do we know if Jann and Ickka had prior sexual contact, although it seems likely. Still, in some cases pregnancy was an issue, but not in the way it sounds. Unlike in almost every other part of Europe, some Aus Friesian families still placed greater value on proof of fecundity than on the dubious benefits of a virgin bride.

The rest of the exchange was predictable. No dowry was offered and none expected. Ickka could take nothing to a marriage but the clothes on her back, her two strong legs and two strong arms. The only question left was one of timing. Obviously, that was soon resolved.

After the two men left Gert might have closed the wooden shutters against the night and whatever moisture dripped beyond the ample eaves and sat back down to finish his beer and stare at the fire. Janna and Ickka would have continued their chores while the younger children, probably banished during the visit to huddle in the animal byres, would’ve crept back inside.

The church at Buhren. Ickka would have been marrried in a similar one.

If not before, in the last few weeks Gerd had certainly made it his business to find out all there was to know about the Buss family. Given the proximity of their villages, this would’ve been a good deal. So, he may well have sat and brooded over the stories of Gerd Buss who had owned a sea-going boat that carried peat to England. With his profits the old man had been able to set up each of his three sons with the means to make good livelihoods. And Jann was obviously a chip off the old block, having a good canal boat and a prosperous business. He’d be wealthy one day.

Yes. The marriage would be a good one for his daughter. None of Ickka’s sons would ever have to take to the road with their scythes on their backs, hoping to find work cutting hay. At this point in his thoughts, Gerd could be excused for feeling a bit bitter since he had no idea how Ickka’s brothers would thrive, yet alone survive as adults. Perhaps by taking to the road with a scythe on their backs, getting work as farm laborers wherever they could find it.

Well. Maybe no. Maybe Ickka would find opportunities for them?

There was no question of Ickka’s acceptance, of course. Gert wouldn’t have consulted her on the subject. Nor is he likely to have discussed it with his wife who, after training and raising the girl, would be losing her labor just when it meant the most within the household. So, how did Janna feel about the whole thing? Probably, not so good.

As for Ickka? She wouldn’t dare complain. Not only would she or her children never want for food or shelter, but she was going to a house with no other women … just the married sister living in the same village.

Unlike most girls who had to move into their husband’s family home and who became little better than a slave to the other women of the house, Ickka would be her own mistress. Well. Slave to her husband and his father first; mistress of the house second.

Ickka would kept her silence throughout, having been trained to it, disciplined to a world where girls do as they are told or are beaten and where the idea of “romantic love” and “happily ever after” didn’t exist. Not for her.

Ickka knew the word “love,” of course. She would’ve heard love ballads and listened to story tellers as they related tales of princes and princesses. She also knew as an abstract concept “love of God” or “love of Christ” and the church’s abjuration about “love of family.” She also knew love as a word used in church to describe the emotional attachments formed between a husband and wife over time. Her mother, she may have thought, loved her father or may have hated him. And may not. After all, it’s difficult to work up strong emotions like love and hate on an empty stomach.

Then there was lust and sexual arousal. She must have known a good deal about that. At Ickka’s age, the wild joy of sex was not forbidden, but it was not seen as a good grounding for marriage and was usually set aside for the test bed of a fiancé. Whether or not she’d had sexual encounters, Ickka knew all about the subject. Her care of livestock and proximity to her parents’ coupling, if nothing else, gave her certain expectations.

How would Jann be as a sexual partner? His hands were large and strong, his body muscular and athletic. On the other hand, she may well have found her mind wandering to the luxury of sharing a bed with just one other person and of having enough quilts over her to keep warm and of a real mattress under her back. The prospect of sleeping warm could well have stirred her more than the thought of the man in bed next to her, although that could be nice, too. She would have to wait and see.

Certainly, Jann Buss was as close as she could ever expect to find to the ideal husband. But Ickka was never one to delude herself, and she would not have done so then. Jann needed an unsalaried laborer. He would expect her to work as hard as she did in her father’s house. Otherwise, why marry her?

Silent and thinking her own thoughts, the newly affianced girl would have no time to either celebrate or mourn her fate but would’ve been expected to keep working, possibly carding wool while sitting on a stool near the fire with her skirt, which would have been far from voluminous, tucked about her bare ankles. Besides dress and apron, she would have had on a pair of wooden shoes and a knit wool shawl. Then, too, women and girls generally sported a plain, snood-like cap of home-made linen that reached from their foreheads to the nape of their necks. Did she possess stockings or gloves, overcoat or nightgown, “small” garments or hats? Unlikely. Instead, she would have made do with a heavy shawl for winter and a prettier one for church plus a ribbon to match. She would also have made herself a proper bonnet that tied under the chin, perhaps even have edged it in lace scraps and made a matching handkerchief to tuck in her bodice for Sundays and festivals.

Ickka’s earliest memories would be of working alongside her mother, of being slapped when her little hands dropped a bucket or for crying when her stomach was empty or her bones frozen with cold. In the winter her nose ran and her hands and feet developed chilblains and her body itched from fleas and lice. When her head ached, which would probably have been often, she had no recourse but to ignore the pain and keep working. Pain, as she no doubt learned in church, was a human’s lot. Pain let you know you were still alive. And, it could always be worse.

To be Ostfriesian was to have a deep understanding of deprivation and hardship because it often was worse.

The mill/shop/tavern at Buhren. One of Ickka’s daughter would marry the owner’s immigrant grandson.

Ideas and words to provoke thought…