Pat Stuart

Books and Columns

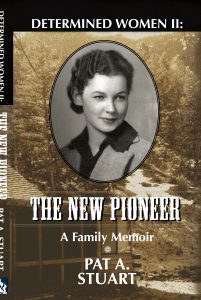

DETERMINED WOMEN – THE NEW PIONEER

Raised in an affluent Chicago suburg by parents who were the product of the Art Institute of Chicago, Marolyn Miller dreamed of a world inhabited by her pioneering ancestors–one that no longer existed, but she strove to recreate for herself. Disappointed in a marriage to a man she’d hoped would be a farmer and saddled with three children, she managed to obtain a lease to a cabin site in the vast, roadless fastness of the Shoshone National Forest. Never having camped out in her life she, nonetheless, took her children and one horse into the wilderness, and there built a 1,200 square foot cabin with hand tools. This is her story. Read the first chapter.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

In 1956, a thirty-six-year-old woman took her three children and one horse into the mountains where she pitched a tent at an elevation of 7,200+/- feet. There, in northern Wyoming’s Shoshone National Forest, she built a 1,200 sq. ft. log house. The design was hers and almost every spike and nail was driven by her.

“I can do this,” she would mutter when a log was too heavy for her to lift or a bear raided the food stores. “I can do this.” And, somehow, she did.

She raised the walls, placed the beams, cut the moldings and fabricated the doors, all with hand tools. She erected it despite her husband losing his job locally and moving to eastern South Dakota. She did this despite raised eyebrows and frank disbelief in the community. She levered logs into place, scavenged granite for fireplaces, survived storms, and faced down bears, all this and much more. “I can do this,” she would say. Beyond and all around her lay continental America’s largest, roadless wilderness.

One hundred years earlier, her great grandmother with four children under the age of six, one still in arms, emigrated to southern Illinois. Within a month of her arrival, her youngest daughter and a nephew were dead, another nephew was permanently crippled, her husband suffered a serious accident, and she had the responsibility of caring for him and her remaining children to ensure they neither starved nor froze. She accomplished this and much more. Twenty years later, ten years after her husband’s death, she was one of the most successful farmers in Adams County, Illinois.

In its entirety, this is a story about determination and perseverance, about one woman’s need to reach beyond the dictates of society and another woman’s determination to survive and thrive. Those women were my great grandmother, Ickka Eilert, and my mother, Marolyn Miller.

CHAPTER ONE

She ruined our dinner and scared us silly when she announced she had to get away. “I’m tired,” she said. “I need a sabbatical.”

The tired part was patently true, but in 1954 America mothers were not expected to need or get time to themselves. Mothers were the glue that held families together. Mothers were attractive and cheerful, wore skirts in the home and hats with veils at church. Mothers were there no matter the circumstances. “I never get sick,” our mother would say. “I can’t afford to. I’m just a little bit tired today.” She was a little bit tired every day, but no one paid any attention until she said she was leaving.

“It’s only that I have to have some time for myself,” she said. The words were an ultimatum not a plea.

She’d decided. She didn’t tell us until much later, but she wanted time to think about what had happened to her father’s daughter, the girl who’d worked alongside the big man in his artist’s studio and in his gardens. “I really wanted to be a pioneer like my grandparents and farm the land,” he’d once liked to say to her. And when she’d answer, “I’ll grow up and be a farmer for you,” he would laugh and ruffle her thick brown crop of curls.

She still had the curls and, although she and her father hadn’t spoken in years, she’d clung to her childhood dream of pioneering type of existence—close to the land, building a life with sweat and personal labor.

“My grandmother never would move out of her log cabin,” Marolyn would say.

Her grandparents and great grandparents had been extraordinary people, according to her father. They’d lived close to the land and both survived and prospered through hard work and self-reliance. “My grandmother never would move out of her log cabin,” he’d told her inaccurately but to make a point. “She milked her own cows and churned her own butter. Oma Buss-Flesner raised her own sheep, and she’d sit by her fire of an evening and spin her own wool. And, everyone said she was one of the best farmers in Adams County.”

Second generation Americans. Marolyn’s grandparents.

Working at her father’s side, Marolyn assimilated his conservative ideology. “People have forgotten how to take care of themselves. Without someone to make their clothes for them, without someone else to grow and process their food, they’re helpless. You just watch. When the next crisis comes, people will die because they’ve lost the basic skills.” He’d run his fingers through the soil of his garden and say, “Learn to do things for yourself.”

How wonderful to create with your own hands and everything you needed. How splendid it would be to live in a house you built on land that provided you with all your needs.

Still, nature as well as nurture shaped her early life and she played with other ideas for her future. She kept scrapbooks full of illustrations, had loved the artist Nell Brinkley’s adventurous girls and Henry Clive’s glamorous cover art women. Maybe she’d be an explorer or, possibly, an artist like Clive, Brinkley, and both her parents.

But years had passed and here she was. It was 1954 and she had a marriage and a life no different than that of millions of other women. Trade her for any one of them and neither her husband nor her children would notice except, perhaps, to see an improvement.

Her mirror said she was still attractive, still could pose for a Clive cover. Her body wasn’t strong, but it could sail a ship or fly an airplane or handle any situation Brinkley might invent. But at thirty-six she was a matron by anyone’s standards.

Thirty-six and her oval face was unlined except for a web of tiny wrinkles in the corners of her eyes and a slight roughening of her ivory-colored skin. Most people saw her even features as somewhere between pretty and beautiful, finding a small gap between her front teeth a charming anomaly, rather like a beauty mark. Then, they would notice the scar tissue cupping her chin. In warm weather it scarcely showed, but the winter cold highlighted ridges of white tracing phantasmagorical designs like the intricate web patterns of a book plate.

Marolyn Dale Miller Reher was on the tall side for her generation at 5’7 ½”. Her fine-boned frame was well proportioned, and she kept her weight down through almost constant dieting. High protein, high carbohydrate foods went on the table for her family while she consumed meals of canned fruit, cottage cheese, and iceberg lettuce, bingeing occasionally on sweets, a diet that didn’t help her problems with energy and depression. Our GP, Doc Dominic, prescribed thyroid medicine and iron tablets, which she mostly didn’t take.

“I’m just a little tired today,” she would say.

She was tired and already half-way through her expected life span and even that thought was exhausting.

What did she have to show for her time on earth?

Life had escaped her control, leaving her stuck with her choices.

At thirty-six she’d learned that each choice she’d made, each door she’d walked through, had taken her further away from anything close to the life she’d once envisioned. It was as though her decision to leave her many-roomed Chicago home, one filled with art and artists, had started her down a road that had carried her, inevitably, farther and farther away from where she was meant to be.

Long ago landscape design had seemed a good way to combine her interests in art and agriculture, and she’d thought that if she attended a School of Agriculture she might even meet a man who shared her dreams of making a life on the land. Oregon State and Al Reher had seemed a perfect fit. Except he changed his mind about his career choice, and then it was too late. She’d already made her promise to “love, honor, and obey.”

Often she thought and spoke in aphorisms and adages. “You make your bed, and you lie in it,” she would say. She had definitely “made her own bed.”

“You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear,” was another of her favorite expressions. It was true enough, but recently she’d been thinking that maybe there were bits of silk stuck in the sow’s ear. Her life in Wyoming had proven a sow’s ear but Wyoming’s mountains? She looked out the picture window of her small living room at the rugged shapes and saw pure silk.

So she took her ‘sabbatical’ in the Absarokas, renting a cabin at Elephant Head Lodge near Yellowstone’s East Gate. There she let the direct rays of a high-altitude sun melt her chronic fatigue, let the sage and pine-scented air stir her imagination. For seven blessed days she thought of nothing and everything, her mind emptied of all her daily worries and concerns. In their place memories surfaced and filled her imagination with notions and ideas that sailed like slow-moving clouds across her consciousness.

Time Outs Can Work … and Did

Amazing what one week could do. In the evenings, watching the antics of flames that both warmed the skin and fed the spirit, she acknowledged a central fact: she was constitutionally incapable of being more than a shadow of the wife her husband wanted. She wasn’t a nurturer or a hostess. For fifteen years she had done what was expected, keeping a clean house, putting meals on the table, entertaining guests, giving her husband three children, and ensuring those children had the same clothing as their friends and as many opportunities as she could manage with the limited resources Al’s salary and her obsession with saving and learned frugality allowed. But the rest? Trying to be what Al and her children wanted took more energy than she had.

She had gone through the motions for so very long. Could she keep it up? Should she? “There’s a world of difference between ‘could’ and ‘should,’” she liked to say, finally deciding she had to learn what she meant. What was the difference? One way or another from now on her life would be different.

The week in the mountains and her isolation did make a difference. Unaware of the way her eyes, which had faded and begun to droop with habitual weariness, regained their color and sparkle and how her lips, which had once curved so pleasantly, recaptured a smile, she sat on a high rock she’d come to call her own and let the land and its lessons seep into her soul. Finally on the day of her departure she looked into the small mirror of her cabin’s rustic bathroom and for the first time since coming to Wyoming she saw the beautiful woman of her wedding pictures.

So she returned from the mountains with sun-rouged skin and a light spring to her stride. She returned to learn that the U.S. Forest Service would be opening up new lease sites for recreational cabins and that her application, submitted years earlier on the mere hope there might be new sites, was due to be processed.

She remembered the story of how her immigrant great grandmother had had to build their first shelter in America because her great grandfather had been incapacitated in an accident and how Ickka Buss had lived in that cabin for the next thirty-odd years. She, Marolyn, could do the same thing.

Soon, she was spending her free time bent over her drawing board, pencil in hand, at work on floor plans and perspectives. “This is how you make dreams real,” she explained to me, letting me watch and at the same time providing a practical lesson in the power of mind over matter. “You draw them.” It was sympathetic magic at its most creative.

Her cabin came alive beneath her fingers. Without doubt she would be one of the lucky recipients of a USFS lease. Without doubt, the drawing would become reality. Someday soon she would sit in front of her own fire in her own log cabin.

“Right there,” she tapped the paper where a funny shape represented a fireplace.

We All Agreed with Her during Those Days

I wasn’t so sure, but I agreed. We all agreed with her on almost everything that winter. We didn’t want her to go away again because the next time she might not come back. Besides, at fourteen years of age, I was still wishing on stars and believing those wishes would come true. For me, the future gleamed like a golden castle lying just beyond the next minute or hour or day. For Mom, the future was a question. Would she be awarded a USFS lease? Could she do … in a minor way … what her great grandmother had done before her?

More to come ….

Ideas and words to provoke thought…